MAY 24 2021: Living Constellation

Debating with myself about whether not rap's real

‘Cause broke motherfuckers are the only ones that have skill.

Debating with myself about whether not rap's real

‘Cause broke motherfuckers are the only ones that have skill.

—BLUEPRINT

Below is the original introduction to Gravity, titled “Living Constellation: An Introduction,” from when it was called something else. I cut it from the final 2017 incarnation and replaced it with a short paragraph because I felt self-conscious. Who’d care? Turns out I would, seven years later. I sometimes miss the person who wrote this. I was ashamed of the struggles that made me special. I didn't even have my own working computer. I’d type up work at Internet Cafes and email it to myself. I think all of it made me a stronger writer.

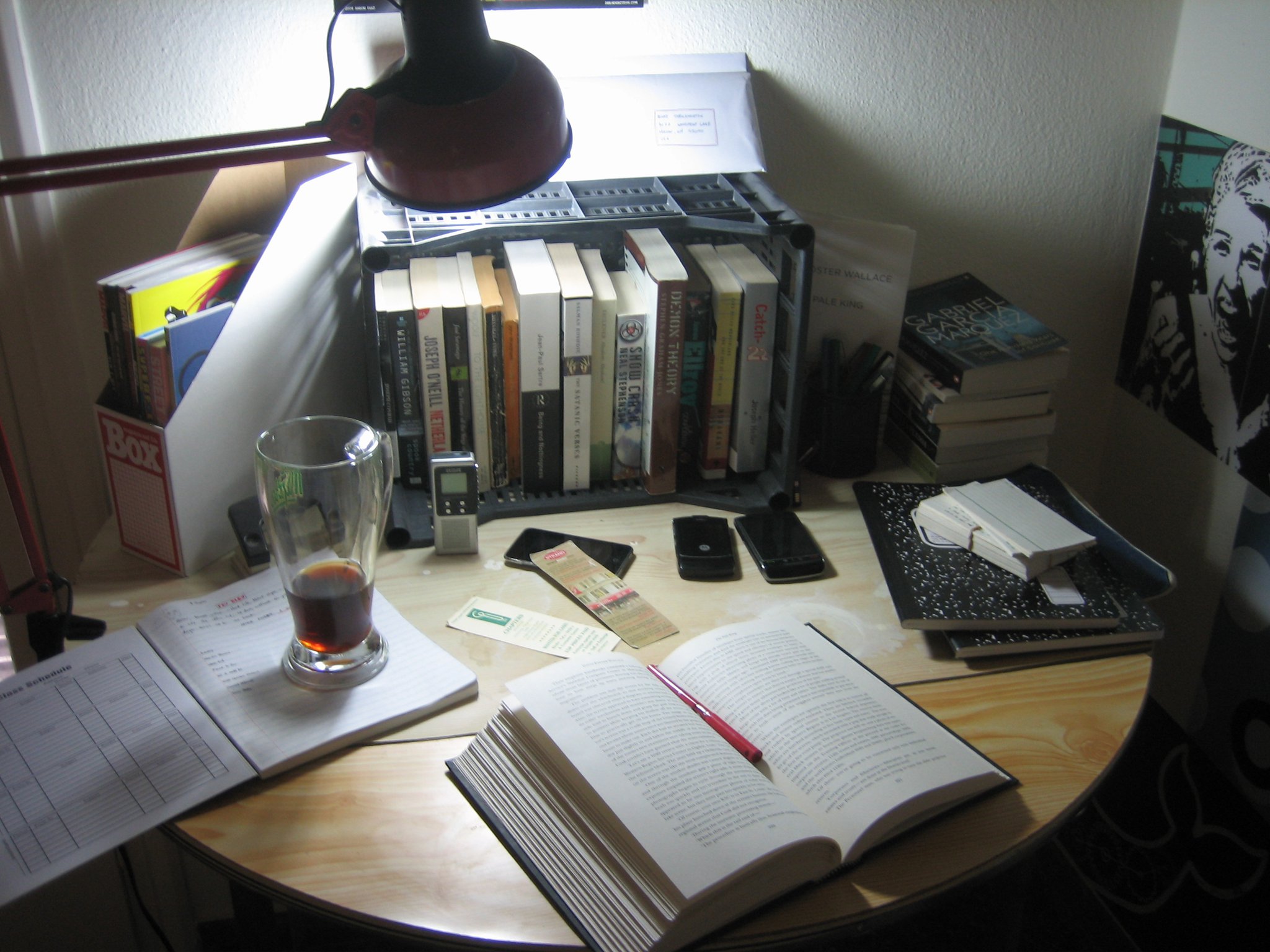

“I wrote my first novel at eighteen years old, and after a process of about seven or eight further attempts, I finally released my first book shortly before my thirtieth birthday. In those twelve years between, I lost almost all of the hundreds of thousands of words I wrote, to hard-drive crashes and weather, and occasional anger. Between the ages of twenty-three and twenty-nine, I moved five times: four cities on two continents. For a while I worked as a night manager at a hostel, reading and working out sentences until dawn, drinking instant coffee I’d spoon into water bottles and shake. I used to sit at the beach or the marina some mornings and dream of leaving—but I’d already left somewhere else and I was in Athens and five years had already passed. What’s strange is I didn’t miss anyone, or if I did miss the people I’d known, there was an understanding that we could live without each other. I was certain then I could survive alone. I felt poor there, not so poor that I was homeless or starving (that would come later, in Paris), but it was poor enough I couldn’t afford to go out except to go to work. Just enough money for a kind of limbo. My desk was a battered old card table and a padded chair I’d repaired with packing tape. There’s an entire year of this time I don’t recall what I was doing, I was drunk all the time and more than okay with that. On a morning I felt spontaneously helpless enough I couldn’t stand it anymore, I bought a ticket and departed a few weeks later, for France. There I sometimes lived between couches, on the kindness of friends I’d made working at the hostel. I spent most of my time in the Pompidou Centre, people watching, studying (I’m an autodidact, if that matters) and working on another doomed novel. Often, I drank wine and contemplated drowning myself in a canal. I used to fantasize about where someone might find me floating. It wasn’t until I returned to the States that things started feeling lighter for the first time in years. I started taking walks. These days I’m more at ease, I live in Oregon, I write slower, I met a good woman . . . you could call it ‘being happier.’ For income, I stock shelves at a hardware store and help people find the tools they need—hey, it’s work. I’m still young and none of this feels as far of a distance as it was. Most of my life’s been improvised. What’s presented here are a handful of the stories that managed to survive. Portland, 2014.”